THE GENIUS OF THE KALAHARI SAN

- curtisnycqueens

- 4 days ago

- 23 min read

Curtis Abraham

A graphic illustration of the San's mythological landscape

Mesmerized by the flickering beauty of the tiny flames, the girl threw them into the night sky, oblivious to the cosmic masterpiece she was creating. Over time, the myth of the creation of the Milky Way (“Via Lactea”) the San girl, and the sparkling embers became an integral part of Kalahari folklore.

This tale was passed down from one generation to the next. The Via Lactea came to symbolize the girl’s eternal connection with the cosmos. As the Milky Way stretches across the night sky, the mesmerizing light serves as a reminder of the San’s rich cultural heritage. What we take away from these tales: is cooperation, respect, living in harmony with nature, and remembering people’s cultural heritage seem not only the very hallmarks of San society, but also those of other hunting and gathering communities elsewhere.

But before the creation of the Milky Way, there was Kaang. Kaang is revered as the creator God. Kaang was the first being, a divine entity that shaped the universe and all living beings within it.

He created a tree with branches that stretched over the whole earth. At this time, humans lived under the earth, and Kaang created a hole at the base of the tree, allowing them to come up.

He then warned them that they could not use fire, and while they agreed at first, the cold nights drove them to do so. So, they made fire and had warmth. But the consequences of this act resulted in all the animals taking flight, scared of the flames. It’s also said that it unintentionally led to conflicts and battle among animals.

Thus, the resulting chaos disrupted the harmony that once prevailed, plunging the world into turmoil and danger. Consequently, humans lost part of their connection to animals, including an ability to communicate with them.

Amidst the mayhem, the San realized the necessity of seeking Kaang’s intervention to restore peace and order. Animals were called upon to approach Kaang and implore for their creator’s return. Kaang was moved and decided to give humanity a second chance.

San mythology emphasizes the importance of harmony and coexistence between humans and animals. Under Kaang’s guidance, strict laws were established to govern human behavior and ensure respect for all living beings. These laws served as a reminder of the consequences unleashed by the chaos caused by fire. Kaang taught values such as respect and cooperation, emphasizing the need to live in balance with nature.

One of the many ways in which Kaang's lessons are best illustrated is through the Ju/hoan San's fascinating relationship with their natural environment, specifically the lions of the Nyae Nyae region of the Kalahari Desert.

While other big predator cats such as the solitary leopard was seen as dangerous and a nuisance, lions were revered, perhaps because they too were social creatures with similar needs as humans trying to survive in the harshness of the Kalahari.

Lions were also part and parcel of San folklore. According to American anthropologist Robert K. Hitchcock of the University of New Mexico, San healers, who claimed shape-shifting powers, would sometimes turn into lions in order to travel quickly to places where sick relatives and friends urgently needed their healing services. https://justconservation.org/the-old-way-and-the-new-way

In 1951, the Marshall family (led by the husband-and-wife team of Lorna Marshall and Laurance Kennedy Marshall) went to South-West Africa (now Namibia) to conduct an ethnographic study of the !Kung of Nyae Nyae (also known as the Ju/'hoansi or Ju/'hoan Bushmen). The journey was officially called the Peabody Harvard Southwest Africa Expedition and would involve multiple trips to the Kalahari region spanning just over a decade.

In 1953, during one such outing in what is today Namibia that the children of the Marshalls,

the late anthropologist and ethnographic filmmaker John Kennedy Marshall, and sister Elizabeth Marshall Thomas, a New York Times bestselling author, witnessed such a remarkable interaction between lions and humans.

"Although the Bushmen treated lions like they treated no other animal, they also manifested so little actual, visible fear of them that they would sometimes take their kill," remembers Liz Thomas. She also noted that the people had no protection against lions. There were neither high protective walls nor robust campfires to keep nocturnal beasts at bay. In addition to shaking burning branches at lions that wandered into San camps at night, the people would also talk to them in a loud, assertive tone telling them to leave, which they eventually did.

John Kennedy Marshall (1932-2005)

In 1953, John Kennedy Marshall, who later became a dedicated activist and advocate for San water and land rights, captured such an encounter between the San and a group of hungry lions on film, which today is part of a collection of his films at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D. C. As Liz Thomas recounts:

"...four Ju/’hoan hunters were tracking a wildebeest they had shot with a poison arrow, only to come upon her lying down, near death from the poison, with a lion and a number of lionesses grouped at a distance nearby. Two other lionesses stood closer to the wildebeest, both watching as she tossed her horns at them. The hunters observed the scene, consulted briefly, then picked up some small stones and very slowly advanced on the nearest lioness, now and then tossing a pebble so that it landed near her without hitting her.

"Speaking calmly and quietly, they called her by respectful names, saying that the meat was theirs and that she and the other lions should leave. Both lionesses stared at the men and at first didn’t move. But as the men continued their slow approach the nearest lioness seemed doubtful, then turned and started back toward the larger group. The other lioness followed. All of the lions paced back and forth for a while, tails twitching, as the men stood still, facing them intently. At last, the lions turned and went away."

(Lions weren't the only animals that were spoken to by the San. According to American anthropologist Robert K. Hitchcock: "In March 2012, Roy Sesana [Tobee Tcori], a G//ana healer and member of the organization First People of the Kalahari, came across a herd of elephants in his garden near Molapo in the Central Kalahari. Employing the principles of the Old Way, he talked to them and told them to leave, which they did.")

Roy Sesana a.k.a Tobee Tcori

These are some of the myths or folktales of the San peoples, the so-called Bushmen of the Kalahari Desert in southern Africa (the term “Bushman” comes from the 17th-century Dutch word Bosjesmans). They are indigenous hunter-gatherers whose ancestral territory included much of southern Africa (the Khoi Khoi or "Hottentots" are San who around the time of Christ and the Roman Empire, started herding goats and sheep and later cattle).

The San are THE OLDEST surviving culture in the southern Africa region according to renowned Canadian anthropologist Richard B. Lee, https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/botswana/foragers-first-peoples-kalahari-san-today. In fact, along with Australia’s Aboriginal peoples (e.g. the Kuku Yalanji of North Queensland, indigenous communities like the San who have also suffered countless massacres), these “click” language speakers are probably one of the oldest human cultures on this planet.

Archeological excavations conducted in South Africa’s Border Cave uncovered numerous artefacts, the oldest dating back to almost 45,000. According to experts, these tools are similar to those used by the San in both historical and modern times.

The Ju|’hoansi of northwestern Botswana and northeastern Namibia exhibit some of the highest diversity in their genetic make-up of any population on the planet. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article/file?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0121223&type=printable. They are thought to have diverged from other humans between 100,000 to 200,000 years ago doi:10.1007/978-3-031-07426-4_3. Their longevity and the longevity of other surviving hunter-gatherers today, is a testament to humanity’s success at adapting to the earth’s harsh environments as well as the capitalistic forces of globalization today.

(According to experts, the San have mixed feelings about genetics-related research. On the one hand there are some who are willing to participate further in genomic research and would like to know the significance of the results, for example as confirmation of the antiquity of their culture and habitation in southern Africa, as well as having their communities reap any financial benefits that might emerge from such scientific investigations. On the other hand, however, some San don’t want anything to do with genetic testing and prefer not to have any blood samples taken from them, opting to be left alone.)

Other than the San, there are still dozens of hunter-gatherer communities around the world whose lifestyles have persisted into modern times: these include the Inuits (“Eskimos”) of Artic North America, the Hadza of Tanzania in east Africa, the Moriori of Polynesia, Mbuti pygmies of the D. R. Congo rainforest, the Fuegians of Tierra del Fuego at the southern tip of South America, the Batek and Penan of Malaysia, among many others.

San today are found both inside and outside the Kalahari Desert. San in South Africa reside in the Northern Cape Region in the area near the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, and !Xun and Khwe San from Angola and Namibia were resettled at what is now a private farm near Kimberley.

The nearly three thousand San in Zimbabwe are found today in the Kalahari sands area close to the Botswana border in the western part of the country, south of Hwange National Park, from which they were forcibly resettled in the 1920s, according to American anthropologist Robert K. Hitchcock.

Like many other African communities geographically severed by colonial boundaries, some San communities inhabit both sides of border areas. The Ju/’hoansi live both is Botswana and Namibia. The !Xun are located in Namibia and Angola. The Khwe live in Angola, Namibia, Botswana, and Zimbabwe. And the Tshwa are both in Zimbabwe and Botswana.

San culture is extraordinarily diverse. In fact, there are at least 50 distinct groups of San spread across the Kalahari and on its frontier. Such communities include the Ju/’hoansi of northwestern Botswana and northeastern Namibia; the G/ui, G//ana, and Tsila of the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR) region of Botswana, and the Tshwa (Shua, Tcua) of western Zimbabwe.

San society, like that of other hunter-gatherer societies around the world, is highly egalitarian. Some writers have speculated that it might have been the first democratic society on earth since there are no kings, chiefs or headmen.

“Each man considered himself as good as the next. All decisions were taken by consensus and only after discussion among all the adults in the family group – both men and women. Once the majority view was established, everyone was expected to adhere to it.”

Dr. Robert K. Hitchcock and wife Melinda C. Kelly. In 2022, the couple established The Hitchcock-Kelly Fund for Human and Indigenous Peoples’ Rights, which provides support for collaborative projects and programs implemented between the departments of Anthropology and Native American Studies.

Despite their myths encouraging a life of harmony and cooperation, their collision with the Western world and that of their African neighbors such as the Tswana has been far from harmonious. In fact, these encounters have been a huge obstacle to their survival as a people.

Like many indigenous and minority communities around the globe, the San have faced colonial domination, ethnocide, racism, discrimination, marginalization, dispossession, resettlement, environmental degradation, and in modern times the forces of globalization (e.g. privatization of land and land reforms as well as changes in wildlife and nature conservation laws including hunting laws).

The KhoiSan were present at the Cape of Good Hope in 1652 when Jan Anthony Van Riebeck of the Dutch East India Company (Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie, or VOC) landed to establish the first European settlement in present-day South Africa. https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/foragers-first-peoples-kalahari-san-today (This encounter literally gave birth to South Africa's so-called Cape Coloreds- children of mixed KhoiSan and Dutch heritage who today number well over 3 million).

The Dutch commander, who was sacked from his post as head of the VOC in what is today northern Vietnam on corruption charges in 1645, and his wife Maria quickly became acquainted with the KhoiSan. One of the first Khoi they met was Autshumao, leader of the Gorinhaikonas (or Goringhaicona) and interpreter to the Dutch who was also fluent in English (despite his usefulness to the Dutch as a translator and KhoiKhoi leader, Autshumato is said to have been the first political prisoner sent to Robben Island for going against the wishes of his colonial masters).

His young niece, Korota, or Eva as she was also known, became Maria van Riebeeck's servant. She mastered Dutch and Portuguese, and was said to have been instrumental in working out terms for ending the First Dutch-KhoiKhoi War.

Right from the outset the van Riebeecks and others should have appreciated the Khoisan for their intelligence, negotiating skills, and the remarkable ability of these click-speaking, African tribal peoples to master European languages to the extent that they became influential translators.

But this was not a peace mission, this was the full yolk of colonial domination in which punitive expeditions and other measures to "show the flag" were part and parcel. Van Riebeeck was Commander of the Cape from 1652 to 1662, and part of his duties was to procure livestock from the KhoiKhoi, the pastoralist branch of the KhoiSan.

Jan Van Riebeck of the Dutch East India Company who ruled the homelands of the KhoiSan by the sword on his left hip.

However, as the Dutch expanded north, they encountered resistance from the herders who required free access to vast amounts of land to graze their cattle and to hunt (the San also needed access to large amounts of land on which to hunt).That had been the norm for countless generations. But the settlers refused to recognize their traditional grazing and hunting rights claiming that there was not enough grass for both groups (Dutch farmers had been given land as part of the policy of freehold ownership where they farmed and lived).

Inevitably, armed conflict erupted into all out war (two wars to be exact) and the KhoiSan were seen as bandits or brigands in the eyes of the Dutch settlers (the same was true for other European colonialist regarding pastoralists populations in the Sahel, East, and the Horn of Africa). It was KhoiSan resistance that led the Boers and Afrikaners to conduct annual extermination raids that also decimated the San population.

"By the end of the 18th century, only 150 years after the arrival of the Dutch at the Cape of Good Hope, thousands of Bushmen (San) had been shot and killed, and many more were forced to work for their colonial captors. The new British government vowed to stop the fighting. They hoped to “civilize” the Bushmen by encouraging them to adopt a more agricultural lifestyle but were unsuccessful. By the 1870s the last Bushmen of the Cape were hunted to extinction. Other Bushman groups were able to survive the European encroachment despite continued threats. The last license to hunt Bushmen was reportedly issued in Namibia by the South African government in 1936.” https://web.archive.org/web/20160314082909/http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0102/feature6/

In the late 19th century and throughout the 20th and 21st centuries violence returned to the San, but not from colonial authorities but state sponsored violence and violence metered out by members of national armies and paramilitaries subsidized by international nature conservation organizations.

The preservationist strategy of nature conservation has seen the San and other indigenous and minorities forcefully booted off their land by usually military or paramilitary forces for the sake of biodiversity conservation ("Fortress Conservation"). Closely connected to the aforementioned approach is what experts call Coercive Conservation ("Green Militarization") that often involves official shoot-to-kill policies (Botswana, Zimbabwe and South Africa have such state sanctioned practices), arrests, detention and sometime torture as deterrents for encroaching on protected land and harvesting its natural resources such as wildlife and plants.

These unfortunate episodes have led to a reduction in land and resources available to the San and other indigenous communities,, higher levels of poverty, lower levels of physical well-being among other blowback.

Today, the San make a living in various ways. For example, the Nyae Nyae and Dobe Area Ju|’hoansi continued to forage up until a generation ago. The Ts’exa, whose homeland once encompassed what is now Chobe National Park in Botswana, and the Hai||om of northern Namibia in the territory of present-day Etosha National Park, practiced a combination of hunting, farming, and herding. The majority of present-day San, like the Omaheke Ju|’hoansi of the Gobabis district of Namibia, live on White farms or in proximity to cattle posts of African neighbors, like the northern! Kung in Ovamboland.

In addition to working on White commercial farms and cattle ranches, and practicing a mixed economy, other San such as the New Xade and some Ju|’hoansi) are part of government resettlement schemes. Others still are attached to non-San villages (e.g. Northern! Kung).

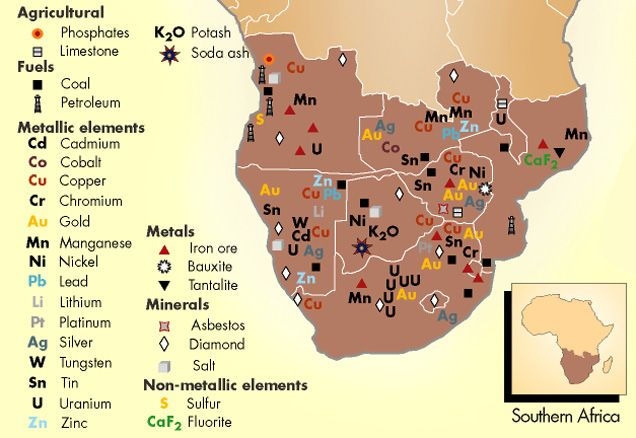

The San continue to face a multitude of challenges including forced re-settlement from their ancestral lands because of the establishment of Protected Areas (PAs) for wildlife, agricultural schemes, road construction, and mining activities.

"In the native communities from the Arctic to the Amazon, in every continent, hunters and gatherers are emerging in the anthropological literature as dynamic and self-determining groups."

So wrote the late anthropologist and scholar Beatrice Medicine, or Híŋša Wašté Aglí Wiŋ ("Returns Victorious with a Red Horse Woman" ) in her Native American Lakota language in the foreword to the Cambridge Encyclopedia of Hunters and Gatherers, edited by Richard B. Lee and Richard Daly.

The various San communities have been at the forefront of this emerging and much welcomed trend in self-determination and national and international recognition.

There are some signs of progress and hope. According to the American anthropologist Robert K. Hitchcock of the University of New Mexico, over the past generation, San communities have achieved some measure of success in organizing themselves both locally and internationally. Community-based San organizations such as First People of the Kalahari (FPK), which is made up of San from the G/ui, G//ana, and Bakgalagadi communities in Botswana; the South African San Council (SASC), and SyNet, which represents the San Youth in Botswana are just a few

Additionally, they have filed legal cases aimed at regaining their land and resource rights in Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa. For example, the San have gained a San from the degree of control over the Kgalagadi Transfrontier Park, in South Africa, along with the rights to park gate receipts. In the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, in Botswana, San (and Bakgalagadi) who were removed in 1997, 2002, and 2005 have obtained the right to return to the reserve. The people also were able to secure the rights to water in the Central Kalahari, which set an international legal precedent. In Namibia, !Kung, !Xun and Khwe San have successfully challenged illegal cattle-owning immigrants who had entered the N≠a Jaqna Conservancy in what used to be defined as West Bushmanland.

The San have also achieved some success in protecting their intellectual property rights (cultural heritage rights). Most notable is the case of the Hoodia gordonii. Hoodia is a type of desert cactus that grows throughout the semi-arid areas of Southern Africa. The San have traditionally used Hoodia stems to stave off hunger and thirst when on long journeys, as it acts as an appetite suppressant.

The South African Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), South Africa’s premier scientific research and development organization based in the city of Pretoria, conducted research on the Hoodia, they isolated the plant’s active ingredient, P-57 and finally registered the patent in 1995 without any attempt at obtaining prior informed consent from the sources of the research lead that led to their ‘discovery’.

Following a series of clinical trials of P-57, which were conducted by Phytopharm, a small British biotech company CSIR had licensed the chemical to in the late 1990s, confirmed its appetite-suppressing qualities. Believing that it would become a weight-loss wonder drug as obesity spreads through the developed and the developing worlds.

This initial success prompted Phytopharm to sub-licensed the product to pharmaceutical giants Pfizer for $21 million. But then Roger Chennells, a lawyer representing the San, found out about the license to Phytopharm of the CSIR P-57 patents. Later, the San, through the South African San Council (SASC) and Chennells, entered into a series of negotiations with CSIR.

In 2002, SASC and the CSIR entered into a memorandum of understanding recognizing the San contribution in the form of traditional knowledge. The benefits were reported to be shared not only with the South African San, but also with San communities in Namibia, Botswana, Angola, Zambia, and Zimbabwe. Although there's much more to this tale, the SASC, according to the American lawyer David Stephenson, received a "token monetary compensation" of around $90,000.

Petrus Vaalbooi, San elder and former chairman of the South African San Council was instrumental in the Hoodia story.

The thorny, finger-like stems of this dwarf shrub are peeled to reveal a fresh, fleshy part that is eaten raw, but is extremely bitter. It is considered a source of healing for abdominal pain. Shepherds and San people used it as an appetite suppressant when travelling long distances. The entire plant is eaten by porcupines.

Some governments in southern Africa have established social and economic assistance for the San and other minorities. In 2007, for example, a San Development Office was established in Namibia. This office is now part of a Marginalized Communities Division (MCD) housed in the Office of the President. This government division provides assistance to these communities in the form of bursaries for children to go to school, school uniforms, food for children and pregnant and lactating mothers, and payment for the construction of water facilities in remote settlements.

There are also numerous nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) working in Namibia assisting the San and other marginalized communities, two examples being the Nyae Nyae Development Foundation of Namibia (NNDFN) and Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation (IRDNC).

The introduction of Community-Based Natural Resource Management programs (CBNRM) have also been a turning point in providing badly needed funds to some San groups. These programs aim to promote the conservation of biodiversity while improving human livelihoods. With the aid of some southern African governments (e.g. Namibia, Botswana, and Zimbabwe) and NGOs, San communities who form conservancies now have legal rights to manage wildlife and benefit from tourism.

In 2018, for example, the Nyae Nyae Conservancy (NNC) made close to $500,000 US for its members, which was generated from a leasehold agreement with a safari company, tourism activities, and from the exploitation of devil’s claw (Harpagophytum procumbens), a plant that grows locally and is exploited both for domestic consumption and for sales to agents who then market the product internationally.

Tourism activities, especially in Namibia, have taken off over the past two decades, but as Hitchcock has pointed out, even such progress has restrictions depending on what country you live is as a San.

"In the case of the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, for example, the G/ui, G//ana, Tsila,

Tsassi, and other communities who are living in the reserve do not have the right to host

tourists, and until recently at least, government requirements were such that tourists visiting

the reserve could be arrested if they entered one of the Central Kalahari Game Reserve

communities (Sapignoli 2018)."

Meanwhile, Non-Profit advocacy organizations such as the Kalahari Peoples Fund (KPF), which was established over half a century ago, has remained at the forefront of assisting the San and other indigenous communities with contemporary challenges including cultural, agricultural, and infrastructure projects.

The organization was founded 50 years ago by the Harvard Kalahari Research Group, and has maintained a priority on bottom-up, grassroots, community-led projects. According to American anthropologist Megan Biesele, KPF's former Executive Director, the secret behind the organization's success and longevity is their friendly and enduring relationship with San community organizations and related NGOs and their staff.

In 2025, KPF’s Executive Director Dr. Jill Brown, outlined some of the planned activities her organization will be involved with.

“This year KPF has been working with eight San communities on projects dreamed up by and for the community. For example, we are collaborating with a Hai//om youth group to preserve cultural heritage through art and dance as well as to and to build small shelters for families most in need in Oshivelo, Namibia. The ≠Khomani San community in South Africa is developing new skills in farming, maintenance and repair work and continue to invest in their youth by creating a remarkably successful soccer league. In addition, exciting proposals are coming together to teach adult language classes in the Ju/’hoansi communities in Namibia.”

A subtropical desert, or an arid, sandy savannah?

The Kalahari Desert is Africa's second-largest desert and the sixth largest globally (it's about the size of Nigeria or Tanzania). Its northeastern region, however, is technically not a desert since it receives double the amount of rainfall a typical desert should receive. The Kalahari is a huge sea of sand contained in a large basin stretching from the Cape of Good Hope north toward the Congo River in central Africa is the environment that they inhabit. The Kalahari covers some 360,000 square miles (930,000 square kilometers), or about the size of Germany, extending across Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa, and encroaching into parts of southern Angola, southwestern Zambia, and western Zimbabwe. Unlike the Sahara to the far north, the Kalahari is covered almost completely with trees, woodlands, and savanna grasslands.

Diamond mines in the Kalahari Desert have forced the San to relocate or live under the occupation of these mining companies.

The San produced ancient rock art in the form of rock paintings and carvings which are typically found throughout the Kalahari in caves and rock shelters. Drakensberg in South Africa and Lesotho are particularly well known for their San rock art as is the UNESCO World Heritage Site at Tsodilo (the “Louvre of the Desert”) in northwest Botswana near the Namibian border in Okavango sub-district. The artwork depicts non-human beings, hunters, and half-human half-animal hybrids. It’s surmised that these creatures represent shamans or medicine men-priest who have acquired their status as healers through the trance dance-perhaps the most important of all the San rituals. https://theecologist.org/2003/sep/01/bushmen-kalahari

As part of their religious practices, the San have a rich tradition of trance dances. During these dances, individuals enter a trance state and establish a connection with the spiritual realm. It is believed that the rhythmic movements and the guiding music of drums and rattles help the dancers achieve a deep meditative state.

"The trance dance of the Ju|'hoansi and other San is a matter of communally-created beauty fostering the altered states of mind necessary to spiritual healing," says American anthropologist Megan Biesele, former Executive Director of The Kalahari Peoples Fund (KPF) based in Austin, Texas.

"Ju|'hoansi say their dances awaken a spiritual substance called n/om, described as healing power. It is energy, a kind of supernatural potency whose activation paves the way for curing. Associated with it are special powers shared with many other shamanic traditions of the world, like clairvoyance, out-of-body travel, x-ray vision, and prophecy. N/om, residing in the belly, is activated through strenuous, artful dancing, beautiful polyphonic singing, and the heat of the fire. It is said to ascend or "boil up" the spinal column and into the head, at which time it can be used to pull out any sickness or unrest afflicting the people in the group. Over half the men in Ju|'hoan society when I was there had experience as healers, as well as a large number of women."

Biesele added:

"The intricate dance steps and the beautiful polyphonic singing combine, in a group art form that usually lasts all night, to include all who are there in the possibility of transformation. Transformations may range from the healing of actual sickness to solutions to social malaise, such as arguments or envy. The dance makes these changes in individuals and groups possible through shared artistry created over whole lifetimes and through interpersonal synchrony that comes from industrious singing and dancing repeated many times in varying, always coordinated forms. I think of this dance, clearly an art with great longevity, as one of the great intellectual and cultural achievements of mankind: individual art can be powerful, but it is even more powerful to be a participant in making shared healing, through delight, possible for all the people one holds dear."

San Rock Painting of a Trance Dance or "Healing Dance"

San culture, like that of other hunter-gatherer societies around the world, is highly egalitarian. Some writers have speculated that it might have been the first democratic society on earth since there are no kings, chiefs or headmen.

“Each man considered himself as good as the next. All decisions were taken by consensus and only after discussion among all the adults in the family group – both men and women. Once the majority view was established, everyone was expected to adhere to it.” https://theecologist.org/2003/sep/01/bushmen-kalahari

A division of labor exists in small-scale hunter-gatherer communities worldwide, and this is the case with the San. San women gather nuts and berries. They also harness natural fibers that can be used for making ropes which are used for traps for capturing small game.

What these communities also have/had in common is that all foods were/are obtained by hunting wild game and/or foraging. Nourishment can also come in the form of wild honey, edible plants, insects, bird eggs, fungi, and so forth.

“A history of hunting and gathering and self-identification as San are probably the best guides to who the San people are”, say cultural anthropologists Richard B. Lee, Robert Hitchcock, and Megan Biesele. https://www.culturalsurvival.org/publications/cultural-survival-quarterly/foragers-first-peoples-kalahari-san-today

However, in modern times hunting and gathering have been outlawed because of the creation of Protected Areas (PAs), for example.

“The Botswana government had abandoned its subsistence hunting licenses in the reserve in 2002, so any hunting on the part of Central Kalahari residents was considered illegal, and dozens of people were arrested, jailed, and fined for engaging in hunting. People were also arrested for possession of ostrich eggshell products, important for craft sales and for exchange with other people both inside and outside the reserve. As one G//ana told me at Metsiamonong in the Central Kalahari in April 2019, “The government criminalized our traditional livelihoods.”

Old hunting kit of the San

The San were semi-nomadic, moving seasonally within certain defined areas based on the availability of resources such as water, game animals, and edible plants https://un.arizona.edu/sites/default/files/2021-11/UNSR_JA_Country_Report_Botswana_2010_English.pdf

Hunting and gathering is a subsistence activity that is not exclusive to us humans, but a common practice among wild animals with backbones that also eat both plants and animals. It’s said to have been practiced for at least 90% of human history.

“Our ancestors evolved as foragers, and all basic human institutions-language, marriage, kinship, family, exchange, and human nature itself- were formed during the two-to-four-million-year period when we lived by hunting and gathering,” writes Richard B. Lee in his book The Dobe Ju’hoansi

Following the invention of agriculture, hunter-gatherers who stubbornly clung to the old ways were either displaced or were conquered by farming or pastoralists societies. But in those San communities that remained intact, the hunting and gathering lifestyle continued.

The hunting kit of the San included a quiver of poisoned arrows and a bow, a spear, knife, springhare hook, and ropes and snares. There was also a digging stick and equipment for constructing a fire-drill.

There were several types of hunting methods. There was the mobile hunt with bow and poisoned arrows. This was done when hunting plains-dwelling wildlife such as gemsbok and kudu (John Kennedy Marshall, the late American anthropologist and documentary filmmaker, famously documented this type of hunt in his 1957 ethnographic film The Hunters)

Another type of San hunting technique was with dogs. This occurred when tracking small game animals such as warthog, hares, and duiker. Well-trained hunting dogs can catch small prey on their own but brings the catch to the attention of the hunter who finishes it off with a spear.

There was/is also underground hunting. This method was done to flush out wildlife such as porcupines, aardvarks, and warthogs out of their underground lairs. San set out in small hunting groups or individually looking for fresh tracks of game animals such as giraffe, kudu, eland, wildebeest, and gemsbok. Once the tracks are spotted, the hunters or hunter quickly scrutinizes the animal's footprints to determine its age and health status to decide whether or not it is worth pursuing the trail (older and sickly prey are preferred since they are slower). During the hunt the men are silent and communicate only with hand signals for fear that any noise would alert the animal to the hunter's presence.

The hunter sneaks up on the animal, sometimes on their elbows and knees, attempting to get within shooting range, about 100 feet of his prey. Once an animal is hit with a poisoned arrow, it can take several hours and up to a full day for the prey to die or become immobilized.

During the tracking and stalking phase of the hunt, San would serendipitously come across leopard tortoises (Stigmochelys pardalis), which can weigh up to 13 kg (29 lb), large snakes or rock monitors that were also a source of protein for the San. Additionally, If the hunters come across an ostrich nest, they drove the adult bird away and collect the eggs and chicks. These were also part of the San diet.

The San are well-known for their neuro-toxic arrow poison. Diamphidia, or “Bushman” arrow-poison beetle, is an African genus of flea beetles, in the family Chrysomelidae. The larvae and pupae of Diamphidia produce a slow-acting poison, which is smeared onto San hunting arrows. The poison takes several hours to a full day to kill or debilitate the prey.

Some of the wildlife traditionally hunted by the San depending on their location include eland, kudu, hartebeest, springbok, impala, duiker, and warthog. They also consumed ostriches and the contents of their massive egg (ostrich eggshellsare used to store water in times of drought and are also used to make beads- a popular fashion accessory in the Kalahari).

Yet another method of hunting, which was the domain of older San men who were less physically mobile, was/is snaring. Although trapping and snaring did not produce as much meat as hunting, it was still and important source of protein for the San.

According to Richard B. Lee:

“A man surveys an area of bush for fresh tracks, then he lays down an unobtrusive line of brush to accustom the animals to cross at certain gaps. The snares are made of rope from local fiber plants with a delicate wooden trigger attached to a bent-over sapling. When the hare, guinea fowl, or small antelope steps in the snare, the trigger releases, the noose tightens and the sapling springs up, leaving the quarry dangling. Snaring does not produce a large quantity of meat.”

Diamphidia beetle larvae

The G/ui and G//ana San (“Bushmen”) of the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR) in Botswana use the garden orb-web spider Argiope. Australis) as a part of the arrow poison repertoire. The San hunters use the contents of the opisthosoma (‘abdomen’) of a spider as sole ingredient of the arrow poison. Scientists are puzzled, however, as to what the source of the poison is since the structure containing the venom-glands, the prosoma, is thrown away. This species of spider is not known to be of any medical importance.

San hunters tracking their prey. They can determine the age and sex of animals by reading the signs they leave behind.

San hunters take down a gemsbok

The San also do a considerable amount of trapping.

.

San hunter retrieving trapped porcupines

The Gatherers

Vegetables harvested by women account for about 75% of their consumption. They rely on their in-depth knowledge of edible, medicinal and poisonous plants. This Indigenous knowledge is passed down from generation to generation. The fact that San women provide three times more food than San men is one of the reasons why women are treated as equals. The San People of Southern Africa - afrocultureblog.com

Comments